How can we write from the perspective of others while still respecting different cultures? How can a children’s book author make money from bulk sales? How is self-publishing in South Africa different? With Ashling McCarthy.

In the intro, Spotify for Authors and Katie Cross on self-narration and email marketing; How do I know when to leave my publisher? [Katy Loftus]; and Claude Styles.

Today’s show is sponsored by FindawayVoices by Spotify, the platform for independent authors who want to unlock the world’s largest audiobook platforms. Take your audiobook everywhere to earn everywhere with Findaway Voices by Spotify. Go to findawayvoices.com/penn to publish your next audiobook project.

This show is also supported by my Patrons. Join my Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn

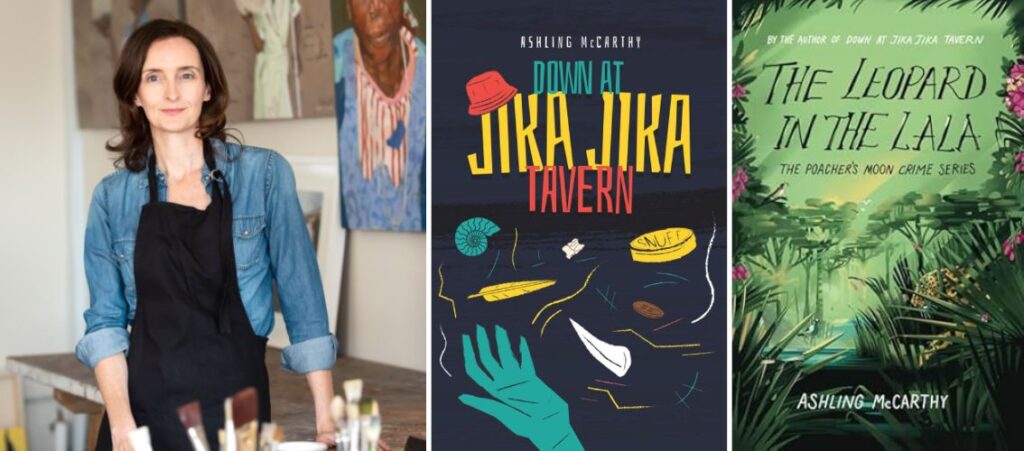

Ashling McCarthy is a South African author and artist, as well as an anthropologist, graphic designer, and non-profit founder. Her latest book is Down at Jika Jika Tavern, in The Poacher’s Moon Crime Series.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- How Ashling’s background in anthropology helps in writing books

- How research can help us write from other perspectives

- The importance of empathy when writing “the other”

- Debunking South African stereotypes and tips for visitors

- The book ecosystem in South Africa

- Difficulties of selling direct in different countries

- Marketing your book to schools and creating teaching opportunities

Find out more about Ashling at AshlingMcCarthy.co.za.

Transcript of Interview with Ashling McCarthy

Joanna: Ashling McCarthy is a South African author and artist, as well as an anthropologist, graphic designer, and non-profit founder. Her latest book is Down at Jika Jika Tavern, in The Poacher’s Moon Crime Series. So welcome to the show, Ashling.

Ashling: Hi, Joanna. Thanks so much. I’m really looking forward to it.

Joanna: Yes, great. So first up—

Tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing and publishing.

Ashling: Well, writing and publishing has come quite late to me. It wasn’t something that I’d ever actually intended on doing. I started off as a graphic designer in South Africa and did a bit of work in the UK, then came home when I was completely homesick.

I got into a really interesting craft development program for people who had a three-year qualification in design, and we would be working with women who lived in rural communities in an area called KwaZulu-Natal, where I live.

As long as you had a three-year design qualification, they’d match you up with women in rural areas who were very skilled at craft. The idea was that then we would work together to match those skills to create high-end product.

So it was really that experience that allowed me to see South Africa in a very different light, and I went on to become an anthropologist and a nonprofit founder. So that took a good probably 15 years of my life and writing a book kind of came out of running the nonprofit.

We’re an education nonprofit, and we work with rural schools. So children who go to really poorly resourced schools in rural communities in in South Africa.

I wanted to write a book for the young women in our communities who didn’t have any examples of themselves in books.

We would get lots of donations from overseas companies for books, but there was nothing that reflected their lives, their experiences. So I thought, oh, maybe I’ll start to write a book that kind of reflects that.

So Down at Jika Jika Tavern is actually the first book in The Poacher’s Moon Crime Series. I, last year, published the second book, The Leopard in the Lala.

How that came about, in terms of writing a crime series versus an educational kid’s book, was that my family was very involved in a game farm with wildlife. Just one day I was thinking about the fact that so many people who live on the outskirts of these game farms have no access to them.

So the only chance of them seeing a rhino or an elephant or any other kind of game is from the other side of the fence, and I kind of wondered what that would feel like. So I started to write a story that would bring that to light.

It was during our time on the game farm it was the height of rhino poaching, and we had six rhinos poached over a period of time. I really started to get a feel for what the book would be about because there were so many interesting incidences that took place.

So for example, a traditional healer was arrested on the neighboring game farm for being involved in rhino poaching. I wanted to understand better, why would somebody who effectively has a calling to do good, why would they be involved in such a heinous crime?

We just had so many little interesting things happen that I was able to then weave these real life stories into fiction to better understand why people become involved in rhino poaching and wildlife crime.

Joanna: Yes, because being an anthropologist, I mean, obviously that means you’re interested in people and what different people do.

Talk about what the job of an anthropologist is and how much you use from your career in the books. What are some of the interesting anthropological things you weave in? I mean, you mentioned the traditional healer. Like, what are the other things?

Ashling: So I must say, anthropology plays a really big part in my writing. I studied Anthro, got a master’s degree in HIV/AIDS and orphan care, and really it was looking at what kind of cultural practices lead to people becoming infected and affected by HIV.

It was really those experiences of understanding how culture can have such a huge impact on the way people respond to certain things.

So now in my books, I mean, obviously, as a South African, we have 11, in fact, now 12 official languages. We are multi-faith, multicultural, so it’s very hard to try and tell a story from one perspective.

For me as a white female Christian, how do I write a story that involves many different cultures, different faiths, different belief systems, without it coming across as judgmental or bias?

So I really do use the methodologies that we learnt in Anthropology, of curiosity, listening, observing, and trying to understand somebody’s perspective from the world that they’ve come from without bringing in my own thoughts and feelings about that. So it’s really interesting and fascinating.

I think it helps to better understand why people do things. Then we can look at—I mean, obviously we want to end rhino poaching and wildlife crime, but just telling people not to do it isn’t good enough. We have to try and help them work with the systems that they have in place that could lead to a reduction in those actions.

Joanna: I love that, and I think that’s so good in terms of whatever we’re writing, whatever genre, taking the perspective of someone else.

I mean, just your examples there, say poaching and HIV, there are some people who might write a story that’s like, “Well, they are evil. They’re the criminal. They’re the bad person because they did this.” Whereas there are some very logical cultural reasons, like good reasons, why these things happen.

I mean, but re-education and changing people’s minds. I mean, even the economics, right? Sometimes this is done because people need it for money to feed their children or something. So this is all so caught up in things that we often just don’t know about.

I mean, this is really hard, though. You’ve spent all these years working with these communities, so you’re trying really hard.

For people listening who want to write other perspectives, how can normal people who aren’t anthropologists with your background write the other?

How can people really try to get into the mindset of someone who just lives a completely different life to ourselves?

Ashling: I think that’s research. I mean, obviously, as I’m writing about poachers, it’s very hard to meet a poacher. They’re either sitting in prison or they’re just totally inaccessible to you. So a lot of research, a lot of interviews, I’ve read a lot of academic papers.

There’s a huge amount of academics that are doing research into wildlife crime and have worked with communities. So I think wherever you can’t physically meet somebody, or even if it’s online, is to really try and read as much as you can.

Also, find people who are representative. I mean, what I know about a traditional healer, which we call an Izangoma here, I know very little about that.

So I found somebody who I could interview and who explained to me what the perspective of that faith and that calling is, and then why somebody might turn from the calling to do good, to do bad. So I think it really is a lot of research goes into it.

It’s not just asking one person. Just because I’m writing about a particular character, and then I interview one person, that’s certainly not the perception of a number of people from that culture or that faith.

In anthropology, we call it triangulation. Finding at least three different sources to verify that information.

Joanna: Oh, that’s really good. I think that’s excellent. As we’re recording this, this will go out a bit later, but we’re in the last week of the American election. It’s just so fascinating to read different perspectives from the polar opposites of a political side of things.

I mean the triangulation in that sense—I know that’s not South Africa, but we all have these same things, right—the triangulation is really hard if you have two extremes and a moderate somewhere in the middle. I mean, with some of these, it’s very, very hard to get into someone else’s perspective.

Is empathy just a big part of it? Like putting aside who you are to try and really listen?

Ashling: Yes, definitely. I think that’s probably the biggest thing that I learned from Anthro was empathy and really just sitting with somebody else’s life experience.

I mean, you talked about wildlife crime and the economics of it. The fact is that I’ve worked and been in communities where really the poverty is just horrendous. People have aspirations just like you or I do, and they want their children to have a better life.

So if somebody’s being offered their entire year’s wages, if not more, for one night to poach a rhino, I mean, very few people would turn that down in order to help their family or to better their family.

Yes, obviously, there is greed and higher syndicates and all of that, but for the average person, or the average poacher who gets involved, I think a better understanding of the other aspects of their life is important.

Joanna: I mean, obviously talking about things like poaching rhinos, I mean this is a normal thing to talk about in South Africa, but most people listening won’t have been to South Africa. They might not know much about it. I think some people might even think it’s an area of Africa, as opposed to a separate country.

What are the stereotypes about South Africa that annoy you the most, or the most dated things you hear about it?

Ashling: Well, I think South Africa gets a very bad rap in terms of, obviously, crime and corruption, and there is truth in that. I’m very much not looking at the country that I live in with rose tinted spectacles.

Yes, there is crime. Yes, there is corruption, but I absolutely love this country. I have no intention of ever leaving.

I think what’s so wonderful about South Africa is the people and how they’re so welcoming and kind and empathetic in many ways. We just have kind of a culture of helping one another, of community, of looking out for one another.

I mean, often when you see videos on TikTok of people mocking South Africa, the first thing that you would notice in the comments is how South Africans, despite race, faith, political agenda, will band together and protect our country to the death. It just really is a country of huge opportunity.

For me, I think it’s really changed the way I view the rest of the world. I have lived in the UK. In fact, my older sister lives in the UK. I’ve got a twin who lives in Hong Kong, and I’ve visited, obviously, on numerous occasions.

I always feel such a great sense of relief and happiness on getting back into that airport at O.R. Tambo and setting foot on South African soil.

Joanna: That’s really great. I worked in Australia in the mining industry with a lot of South Africans, who I guess they must have left in the 90s, which was a different time, obviously. I feel like when people say South Africa, they have Nelson Mandela in their head, which is what, 20 or 30 years ago?

Ashling: Yes, 30 years ago this year.

Joanna: 30 years ago, yes. It’s a very, very different time. As you said, I guess the other thing we hear is the crime for travelers. So if people want to travel—

Do you have any tips for people who might want to visit South Africa?

Ashling: Absolutely. Like any country that you visit, there are areas to avoid. There’s just the simple rules, like not going into the CBD, the Central Business District, late at night. I mean, there are very clear areas that you shouldn’t visit during the evening.

I know everybody loves to flock to Cape Town. Cape Town is amazing. It’s beautiful. It’s got wine farms. It’s got the mountain. Absolutely stunning, but it’s quite interesting, a lot of non-Capetonians feel it’s a very different experience. Like when I visit there, I always feel like I’m in a slightly international kind of zone.

Areas like where I’m from, Durban, a lot of people bypass Durban because Durban does have a bad rap. It’s worth visiting Durban though. I mean, we are two hours away from the mountains. We’re two hours away from game reserves. We’ve got the beach on our doorstep.

My suggestion is to look around at the other places and other locations to visit. There’s the Karoo, there’s the Kruger National Park, which obviously a lot of international visitors flock to as well.

So I think just do your research and try and get on to maybe some South African groups that can share with you some of the best things to do and maybe some of the places to avoid. There’s quite a lot of those websites.

Just thinking about what you were saying about Australians and South Africans in Australia, I think probably the worst ambassadors for South Africa are those that have left. Many have left for good reason, better job opportunities, or maybe have had a traumatic experience in this country and often don’t represent us well overseas.

I think to look past that, as that’s the same for virtually every country in the world.

There’s the good and the bad, and we have to look for the good and explore that.

Joanna: Yes, I totally agree. I mean, obviously there are dangerous places in any country in the world, so I think that’s important to stay. Also, I totally agree with you with going home. It’s interesting how you talk there about going back.

I mean, I lived in New Zealand and Australia between 2000 and 2011, and you know, there were reasons that I was away. Jonathan, my husband, is a New Zealander, and both of us are so pro the UK. I’m so English now. I feel like I am English, not just UK, but I’m English.

I think going away, like you also lived away, going away and then making the decision to return, it means you make it like an active choice to live in your country. That’s huge, isn’t it?

Ashling: It’s a very, for me, an intentional commitment to the country. Also, I mean, I was born in the very late 70s, so I had 10 years of apartheid South Africa. I understand how privileged our position was at that time, and still is, and wanting to contribute back to the country that allowed me to become the person I am.

That was part of running the nonprofit, was saying there are so many kids out here who deserve better. If I can contribute to that and make something happen there, then I actually owe it to this country.

It’s been a very intentional decision to return here and to make the best life possible, not just for myself, but for those around me.

Joanna: So let’s come on to the books and publishing side.

Tell us about the book ecosystem in South Africa.

Do people use like Kindle and the Kobo? How do they listen or read? What are print sales like, as well?

Ashling: Yes, Kindle is definitely big here. I still get into arguments with people about Kindle versus physical books, and there’s still a lot of people who want to have the book in their hand and smell the paper and all of that. So I would say both are used widely.

I, personally, haven’t heard too much about Kobo, but that could just be because I have a Kindle, so I don’t listen out for that. Ebooks, as far as I know, it’s through Kindle.

I’ve started looking into, after listening to the talk with yourself and Adam Beswick about selling direct, I didn’t realize I could sell ebooks directly from my website. So that’s something I’m exploring now as well.

Audiobooks and Audible is very popular here as well. So, yes, I would say there’s still a big physical store presence, like to go into a store and buy a physical book. Books on Amazon, yes, downloading ebooks.

To order a physical book on Amazon, the courier fee is very prohibitive to get a physical book from international to South Africa. So that probably isn’t too big, but I mean, all the bookstores here sell whatever it is that you are looking for.

Joanna: If somebody wanted to sell their books in a South African bookstore, is it a chain?

Is it mostly independents? Is that something you’ve looked into, or is it dominated by publishers?

Ashling: So in terms of self-publishing, in order to get your book into big bookstores, like Exclusive Books, or Bargain Books, or whatever it is, you have to work through a distributor. So there are probably about three or four distributors.

The big chains won’t deal with you as an independent author. They want to work through the distributor. So the distributor, they read your book, and then they either accept it or reject it. If they accept it onto their list, then you would send your books to them, and then they approach all the big chains.

They also work with schools and other entities, but it has to be done through that distributor. So what that does mean, though, as an independent, I’m still not coming out with a huge amount per book.

The bookstore gets quite a big discount so that they can sell it at your retail price. Then the distributor takes a big chunk of that. Whatever you’re left with, then you obviously minus your expenses off of, and you’re left with that little amount as a profit.

Joanna: Yes, print books are a very challenging situation. Well, those same chains, do they work across Sub-Saharan Africa in general, or is it like a South African thing specifically?

Ashling: Some of them do. I’m thinking of two very big ones that would probably work in Namibia, Botswana, those countries that are quite close to us, but I don’t think through all of Africa.

Joanna: You mentioned earlier that there are 11 or 12 languages just in South Africa, and obviously every other African nation has a whole load more languages. I mean, there’s a lot of them.

You’re publishing in English. Is that what people usually do, or are there publications in other languages?

Ashling: English and Afrikaans would probably be the two main languages to publish in. There is a push towards indigenous languages, like IsiZulu, isiXhosa, some of those other languages that some authors might want to publish in.

English is taught through in most schools. So, generally, everybody can read English or Afrikaans. Those are the two biggest languages spoken in the country.

Joanna: What about self-publishing in South Africa?

If people listening are in South Africa or they’re interested, what are the specific challenges? Are you using exactly the same stuff as I would, or an American would? How does that work?

Ashling: So self-publishing, it hasn’t been too difficult in terms of just setting it up. I mean, you get your ISBN from the National Library System.

Then I went straight to Amazon, in terms of wanting to reach an international audience. So I have the physical book and an ebook, so that’s not difficult to do.

Now that the payment systems have changed, prior to about a year and a half ago, your payment would have to go through an American bank account. Then you would withdraw that to a South African bank account. Now you can be paid directly from Amazon, which is fantastic.

Then the actual physical books here, I work with a local printer, and I do runs depending on how many books I need. That can be quite costly, obviously, because we’re not printing thousands of books, but I’m sure that’s the same for print on demand anywhere

I haven’t really found anybody yet here who does print on demand to say that I just want 10 books and for it to be cost effective.

So what I do is some of my books I will work through my distributor, and then other books I will have for myself. I do a lot of art shows. If I do a book launch or a talk, I will take books with me and sell directly to the public.

Joanna: You mentioned your online store as well. What have the challenges been with selling direct? A lot of people listening, they’re not in the US, they’re not in the UK. I mean, even people in Europe are struggling with some of this stuff.

What are some of the difficulties with selling direct?

Ashling: Really, around payment. So, I mean, I’m quite new to this part of trying to reach an international audience outside of Amazon. I wanted to move away from people being able to only buy via them.

So it was interesting, as I said, when I listened to Adam Beswick’s talk of how he’s doing sales directly from his website, my first challenge there was, well, who am I going to use to print these books? How do they get delivered to people? How do I get paid for that?

I was really trying to work out what is the best platform, and it seems to be somebody like Ingram Spark that can do all of that for you. The distribution, the printing, so I’m looking into that.

Then, you know, if I use a BookFunnel for ebooks, then just ensuring that my website is aligned to BookFunnel’s way. It’s just trying to work out the technicalities of how these things work together.

I’m very much listening to a lot of your podcasts and trying to learn from what people have already done. I think that’s probably the best way to do it is find people who are doing it, and then just email them and ask them and hope that they will email you back.

Joanna: Yes, I think that’s a good call. I mean, I’m using Shopify. I think Adam uses Shopify.

Are you using Shopify or an ecosystem like that, or are you trying to do it just straight from your website?

Ashling: So it’s straight from my website, which does have an ecommerce platform.

I did speak to my web person about this. Like, should I rather just start a different website? Also on my website, I am an artist, and so it’s almost like a multi-disciplinary website. Should I rather have just a website for my books?

She said, well, the issue with that is that you really have so much SEO and traction and articles linked back to your original website. You would lose that when starting a new website.

It’s those kind of little things that I obviously wouldn’t think about because I’m not a web person, and my tech side is very poor.

I think it’s even just finding out those little issues that could kind of create a hassle or an issue as you try and build the book business away from your original author page, or whatever it might be, and then trying to figure out what the solution is for that.

Joanna: It’s definitely a challenge. I mean —

My answer on that because, obviously, I have separate websites, is just to put links on the main site pointing at the other site.

Redirection onto another site, and then have call-to-action. So there’s ways around that.

The other thing is, like you mentioned Ingram Spark for print books, and I think there’s no integration that I know of that will be just one click where they just go straight through to Ingram. So at that site, you’ll have to get the orders manually and then load them up separately.

Ashling: Yes, so it’s quite challenging. I don’t think I had any idea of what lay ahead.

Also, because it happened quite—not suddenly. It took eight years to write the first book, but when you write in the book, you’re not thinking about how am I going to get it out into the world? You’re just impressed that you actually finished it.

So trying just to work out —

How do I now take this seriously? Because I can’t keep writing books if nobody’s buying them. I do have to also make a living from what I’m doing.

So something that I am very focused on, and it might not work for everybody, but it certainly does work for me because of the content of my books, is that they are perfect for high school English set works. The content is very relevant to the social, economic, political, conservation challenges faced in South Africa.

I have got the book into two schools, so my marketing focus is actually on books and schools.

Then also the services that can benefit kids in terms of writing. So one school has taken books, and then we’ve written a teacher’s guide and a student workbook, which will be out next year, so then the teacher can really engage with the material.

Then they’ve asked me to come and do a narrative writing workshop because apparently kids today don’t know how to do creative writing because they’re always on their phones and they’re not actually reading.

How can you create other services that complement your writing and the sale of your books, but actually broadens your income generation strategy.

Joanna: I think that’s great. In that way, as much as I love Adam Beswick, I don’t think that model is for you.

I think the bulk sales model is for you, and exactly what you’re doing in schools.

A few years ago now, I had an interview with David Hendrickson, who has a book about how to get your book in schools. He has a book, How to Get Your Book Into Schools and Double Your Income With Volume Sales. I’ll link to that in the show notes, or search the back list for David Hendrickson.

He talks exactly about that. I mean, also Karen Inglis has been on the show talking about books in schools and doing that. As you say, I mean, when you think about the fact that you do have to make a living, you don’t want to grind it all out to get a couple of sales on Ingram Spark when it’s difficult to do.

Whereas you can sell 50- 100 books into a school and then go and make some income from teaching as well.

So I think that’s definitely the way to go.

Ashling: Yes. Even that photo that I sent you of all those books that were going out, I had been very lucky too.

I’ve been in the nonprofit sector for so long, I also understand the landscape of charity and donation giving, and how corporates in South Africa must give a percentage of their profit to charities in order for their scorecard to be up to date.

I was able to approach a funder, an environmental funder or company, and say to them, “I have these books. Are you interested in encouraging reading in schools, but also working with conservation organizations?”

There are two really big training organizations here for wildlife conservation, and they very happily purchased 250 copies, which then were handed over to those colleges so that their conservation students could read the book and learn about community interaction and how important it is.

That was a great opportunity for me to get my books into those. So I got paid. The company gets what is called an SED certificate.

The organization has a resource that they can use, and that also I can then work with them further going forward, in terms of training, workbooks and workshops. That’s a really nice opportunity for both them and for me.

Joanna: I think that’s great. Like you say, schools want to do this, and charities want to do this. This bulk sales model, I realize I focus a lot more on the sale to the end customer, but —

This bulk way of book sales, particularly if you have a book for schools, is just brilliant.

So more people should definitely think about that, because as you said, you probably got that money—Did you get the money before you even printed?

Ashling: Yes, I don’t print until I get paid.

Joanna: The cash flow situation is just a lot better.

Ashling: Much better. Yes, as you’re not seen sitting with boxes and boxes of books and hoping that somebody’s going to relieve you of them over time.

Joanna: Exactly. I think this is the thing to think about book sales. I mean, none of those sales of those 250 books, they’re not going to appear on any best seller list, but that’s not the point. As you said, this is a living for you, so that’s what we have to think.

It’s bank, not rank.

Ashling: Absolutely.

I’m really not too concerned about being famous, that might have been in the back of my mind at one point, but it’s really that I just want people to be reading the books. I specifically want high school kids to read them. I mean, it’s written for adults, but it’s great for high school.

I love meeting people who’ve read the book and their minds have shifted. Their mindset has shifted, or their view has shifted on this topic, and they can be a bit more empathetic and kinder. That’s really the point of it.

Joanna: Just on marketing. Obviously, we’ve talked about the schools there, but as you said before, you’re also an artist. You have physical art. You mentioned there a bit about SEO.

How are you marketing the books, and also the rest of your business, in South Africa and globally?

Ashling: I’m not very good, I must say, at marketing.

I think I definitely fall into the Gen X of hating self-promotion. I know I should probably be on TikTok and all of those kind of platforms, but I use mainly Instagram. Facebook, I have an author page.

I think that’s how my focus on the schools came about, when I realized this is not a strength of mine, of marketing and really posting every single day, and kind of trying to get people to become interested in the book. So actively pursuing schools is one way to get around that.

For art, I will attend art exhibitions. So we have quite a number of them throughout the year, which are like three or four day events which you can attend and have a stall.

I must say though, that art, as much as I enjoy it, it’s not my focus anymore. If I have the time to paint, I’ll definitely paint. I’ve realized throughout my entire working career —

I very much had an approach of trying to run three or four things at one time. Now in my 40s, I realize it’s overwhelming. It creates extreme burnout.

Actually, maybe I could just focus on writing. It’s what I love doing. With art, so for example with the student workbook, I can illustrate that workbook and use art in that way. It’s kind of a complimentary service to the writing and not just always stand alone.

Joanna: I think that’s great. I only laughed with what you said about the marketing because pretty much everyone feels that way. I really don’t know many people who are like, “Oh, yes. I love marketing, and I’m so good at it.” Not many authors do that. I was going to ask you—

What about the audiobooks?

Ashling: Yes, I am desperately wanting to do an audiobook. It’s very expensive here. I don’t know if it’s hugely expensive on your side. It’s definitely something I get asked a lot about.

I think, again, it would complement high school, especially for kids who don’t want to read the book, or maybe they have a learning disability or challenge. So, actually, the audiobook would be perfect for them. So I’m in the position right now of going, do I actually just record one with me reading it?

Joanna: Yes, I was going to say exactly that. I mean, I love the South African accent. People listening can hear that you’ve got a lovely voice. Is your protagonist female?

Ashling: She is a female. My only kind of reticence about doing this is that she, while there are many characters of different races and cultures, she is a black female. I really wanted to have a young black female do the reading of the book.

It’s been suggested to me, why don’t you just put the first book out and your voice? Then when you are able to pay for a proper recording with a professional narrator, then do that. So I think I might do that just to get it out there.

Joanna: I think that’s a really good idea. As you say, the practicality of finding the exact perfect person for that voice, that’s going to be really hard. So it’s known as just the narrative straight read, the straight read by the author. Quite a lot of people do it.

I’m starting to do it more. I’ve mainly done my short stories, but I have thought about just doing my novels as well. You don’t have to make up voices and things like that, you don’t have to do accents. It’s just a straight read, as if you were reading it in schools.

Do you do readings in schools already?

Ashling: No, not a lot, not yet. I will be as of next year, as I go into the schools. I do readings at book launches and stuff.

Joanna: Yes, exactly. I think that recording your own audio now, the software to do the mastering and stuff is good. So for people listening, Hindenburg Narrator is the software that I recommend now. It just gives you a one-click output for ACX and Findaway Voices.

So I would agree with people who say to record it yourself. Then if you make enough money, and if you find someone—I mean, maybe in one of these schools you’ll find a young black woman who wants to act or wants to get into that. That might also, in itself, be an interesting opportunity.

Ashling: A great opportunity.

Joanna: I’d encourage you with that, and I love your voice. I’ve always liked the South African accent. Okay, so we are pretty much out of time.

Where can people find you and your books online?

Ashling: Well, if you’re South African, you can just pop over to my website, www.AshlingMcCarthy.co.za. Then, for now, I am on Amazon, both Kindle and Kindle Unlimited.

I am probably not going to be on Kindle Unlimited for too long because I want to try opening up the ebooks to other platforms as well. So for now, my South African website or Amazon.

Joanna: Fantastic. Well, thanks so much for your time, Ashling. That was great.

Ashling: Thanks, Joanna.

The post Writing The Other And Self-Publishing in South Africa With Ashling McCarthy first appeared on The Creative Penn.